African Americans

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Official Site of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- BlackPast - African American History Timeline

- Constitutional Rights Foundation - An Overview of the African-American Experience

- Smithsonian Channel - To Shatter the Foundations of White Supremacy

- PBS LearningMedia - Michael Strahan: Second Middle Passage

- PBS - Sharecropping - Slavery By Another Name

- Minority Rights Group International - African Americans

African Americans, one of the largest of the many ethnic groups in the United States. African Americans are mainly of African ancestry, but many have non-Black ancestors as well.

African Americans are largely the descendants of enslaved people who were brought from their African homelands by force to work in the New World. Their rights were severely limited, and they were long denied a rightful share in the economic, social, and political progress of the United States. Nevertheless, African Americans have made basic and lasting contributions to American history and culture.

At the turn of the 21st century, more than half the country’s more than 36 million African Americans lived in the South; 10 Southern states had Black populations exceeding 1 million. African Americans were also concentrated in the largest cities, with more than 2 million living in New York City and more than 1 million in Chicago. Detroit, Philadelphia, and Houston each had a Black population between 500,000 and 1 million.

Names and labels

As Americans of African descent reached each new plateau in their struggle for equality, they reevaluated their identity. The slaveholder labels of black and negro (Spanish for “black”) were offensive, so they chose the euphemism coloured when they were freed. Capitalized, Negro became acceptable during the migration to the North for factory jobs. Afro-American was adopted by civil rights activists to underline pride in their ancestral homeland, but Black—the symbol of power and revolution—proved more popular. All these terms are still reflected in the names of dozens of organizations. To reestablish “cultural integrity” in the late 1980s, Jesse Jackson proposed African American, which—unlike some “baseless” colour label—proclaims kinship with a historical land base. In the 21st century the terms Black and African American both were widely used.

The early history of Blacks in the Americas

Africans assisted the Spanish and the Portuguese during their early exploration of the Americas. In the 16th century some Black explorers settled in the Mississippi valley and in the areas that became South Carolina and New Mexico. The most celebrated Black explorer of the Americas was Estéban, who traveled through the Southwest in the 1530s.

The uninterrupted history of Blacks in the United States began in 1619, when 20 Africans were landed in the English colony of Virginia. These individuals were not enslaved people but indentured servants—persons bound to an employer for a limited number of years—as were many of the settlers of European descent (whites). By the 1660s large numbers of Africans were being brought to the English colonies. In 1790 Blacks numbered almost 760,000 and made up nearly one-fifth of the population of the United States.

Attempts to hold Black servants beyond the normal term of indenture culminated in the legal establishment of Black chattel slavery in Virginia in 1661 and in all the English colonies by 1750. Black people were easily distinguished by their skin colour (the result of evolutionary pressures favouring the presence in the skin of a dark pigment called melanin in populations in equatorial climates) from the rest of the populace, making them highly visible targets for enslavement. Moreover, the development of the belief that they were an “inferior” race with a “heathen” culture made it easier for whites to rationalize Black slavery. Enslaved Blacks were put to work clearing and cultivating the farmlands of the New World.

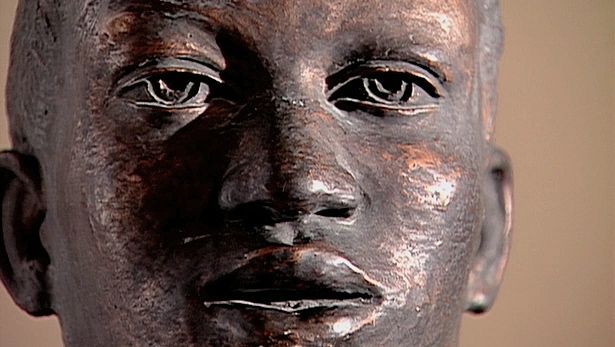

Of an estimated 10 million Africans brought to the Americas by the trade of enslaved peoples, about 430,000 came to the territory of what is now the United States. The overwhelming majority were taken from the area of western Africa stretching from present-day Senegal to Angola, where political and social organization as well as art, music, and dance were highly advanced. On or near the African coast had emerged the major kingdoms of Oyo, Ashanti, Benin, Dahomey, and the Congo. In the Sudanese interior had arisen the empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai; the Hausa states; and the states of Kanem-Bornu. Such African cities as Djenné and Timbuktu, both now in Mali, were at one time major commercial and educational centres.

With the increasing profitability of slavery and the trade of enslaved peoples, some Africans themselves sold captives to the European traders. The captured Africans were generally marched in chains to the coast and crowded into the holds of slave ships for the dreaded Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean, usually to the West Indies. Shock, disease, and suicide were responsible for the deaths of at least one-sixth during the crossing. In the West Indies the survivors were “seasoned”—taught the rudiments of English and drilled in the routines and discipline of plantation life.